One day this past summer, I came home from work to find a letter wedged in the crack of the heavy steel door that I have lived behind for the past six years. Like so many that bear bad news, it was folded neatly into thirds.

The letter informed me that I was a month and a half late on my rent, and if I didn’t pay my balance in 30 days, the property company that owns my 100-plus-unit building would begin eviction proceedings.

I’d known this was coming, in some ways for a very long time. In the past eight years, my salary, which had nominally increased from $55,000 to $64,000, had, when adjusted for inflation, in fact been decreasing, just as rents continued to rise.

There is nothing particularly tragic or unique about my circumstances: I live in a one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, a marker of a middle-class lifestyle I had hoped but failed to attain by now, at age 36. I’d noticed, in the past couple of years, friends and acquaintances finding themselves at a similar juncture: one, at 35, moved back in with a roommate. Another told me the rent increase on their apartment meant, without a better salary, they would run out of money within the year.

The pandemic, which caused a citywide rent increase of 33%, might have played a role in this outcome. As might my choice to work in the media industry. “You can’t eat prestige,” my friend in similar circumstances likes to joke. And it is true that I could have spent more wisely, freelanced more often, and saved more judiciously. But, with things on their current course, addressing these factors would only have delayed the inevitable arrival of this piece of paper in my door. In the long term, the math just wasn’t there.

Though I hadn’t seen it at the time, somewhere in the 15 years since I’d graduated from college and moved to the city, my expectation for a stable, middle-class future lost touch with the reality of my circumstances.

Back in 2008, I moved with friends to a two-story house in Brooklyn not far from where I live now. It had four bedrooms, a driveway, and a quiet, overgrown yard. It had a nice sunlit kitchen where we stayed up late playing Risk, smoking cigars, marching around the table like generals. It had a big living room with an old fireplace and a stained white couch where two of my housemates spent most of their time arguing, often throwing books about socialism at one another.

We also had mice. Our landlord’s solution was to drop off a small bottle of cinnamon oil and tell us to rub it on all the floor boards. It never worked, nor did anyone think it would. The mice remained, crawling on the stove and occasionally wandering out into the living room to die once our neighbor began poisoning them. Our landlord always had a new plan for the mice but never quite put anything in motion. We didn’t fault him for it, because we all had an understanding: we paid $550 to live there, deposited the cash into a bank account number, and didn’t cause a fuss about rodents or clogged tubs. Eventually, so was the plan, our incomes would improve and we would move out and on with our lives. Our landlord’s income would go up and he and his wife and children would leave their rental apartment and move into the house. He never cared if the rent was late.

To my memory, these arrangements of shared inconvenience were common in those earlier years. I would go on to live with a woman who owned two blind albino rats that would hide in my room once her boyfriend from Minnesota moved in with his Bengal cat. Later, I lived with a guy who had run away from his home in Oregon and was sleeping in a space he created in the living room by hanging sheets from the ceiling; he wanted to save money by renting his room. He had plans to open a fruit smoothie store, but mostly he just smoked weed and talked strawberries. I woke up one morning to find the front and back doors open, leaves blowing through the house, which appeared to have been ransacked. I never bothered him about it, and he charged me very little to live there. How much exactly I can’t recall. The only record I have of the transaction is an email containing a phone number and a note that read: “I am willing to work out a round figure for rent.”

I met so many kind people during those years, all hopeful that better things were just around the corner. Sometimes, they were: one of my landlords was a model who gave up on living with other models after one of them overdosed and died in their bathroom in London. She said I could stay as long as I liked provided I didn’t complain about there being no hot water. When I left, she handed me a Jamaican dollar with “the sky is the limit” written on it. I sometimes see her in movies on Netflix now.

As I grew up, my desire for the trappings of a stable, comfortable life also grew, if not the means to achieve them. In 2010, I moved to San Francisco after the magazine where I had worked in New York ran out of money, shed most of its employees, and began referring to itself as a data-visualization company, before eventually redirecting its webpage to a site offering free desktop wallpapers.

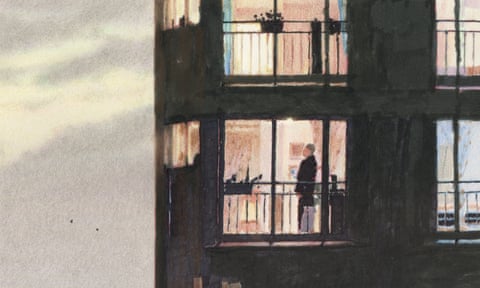

While in California, I at one point lived alone for the first time, in a room on the third floor of an old Victorian house. I couldn’t really afford it working as a factchecker, but I clung to it. It had a deck where I often watched the sun rise over the Haight. Down the hall from me was a woman who was about 80 years old. I never saw her leave her apartment. A few times, someone would come by and bring her groceries. Through the crack in the door, I’d see stacks of newspapers and old corner-store bags. I’d see the same thing years later, in my current New York building, with an old man on the third floor who would always ask for DVDs and copies of the New York Times until one day I stopped hearing from him.

At the time, in San Francisco, I would wonder to myself why an elderly person who had such trouble walking would stay on the third floor of a creaky house. What I think I might be starting to see now, a decade later, is that there is no guarantee you can ever return to a place you leave. Perhaps the old woman went to California in the 1960s, believing in what that generation believed in. Perhaps she was born there. Perhaps she couldn’t afford to move elsewhere.

I’ll never know. But I suspect she knew that if she left, the door would lock behind her.

As summer turned to fall, the 30 days that my demand notice had afforded me came and went, as I knew they would. By then, I was months behind. I asked my landlord company for more time, but they never replied.

A week later I came home from work to what I had long expected: a notice in my door informing me that I was being sued in Brooklyn’s civil court. Up to that point in the year, about 2,100 households a week in New York City had come home to these suits, and so the neighbors who saw that pink sheet of paper on my door all knew what it meant: barring a financial Hail Mary, my time would soon be up. Not long after, my super, whose job it had been to stick the eviction suit in my door, began asking me “are you OK?” every time I passed him in the hall. In the elevator, a neighbor on my floor would often tell me that New York just wasn’t worth the price tag any more.

I’d spent years sharing the building with my neighbors, and the thought of losing them weighed on my mind. There was the woman on the fourth floor whom, last fall, I ran into at my corner store. She asked me if I would be seeing any family on Thanksgiving, which I wouldn’t be. A few days later she rang my doorbell with plates of macaroni and cheese and mashed potatoes. The summer before, I had let my neighbor across the hall borrow my guitar and she returned it with a jar of granola. Months later, she invited me to her Thanksgiving as well. And frequently the woman who lives next door will text to let me know she is dropping off a paper bag full of vegetables that she picked from her community garden. Now, she and her husband feed my cats when I am away.

We all have these stories, of course. I just rarely considered them before the eviction papers arrived at my door.

On the front page of the suit was a letter informing me that I had 10 days to appear at the civil court clerk’s office to set a date for my hearing. If I failed to do so, a judge could evict me immediately. Looking at the filing date on the notice, it appeared that my landlord waited five days to deliver the paper to me. The process, which up to that point I had understood as the sad but justified efforts on my landlord’s part to collect what I owed, felt like something else: an opportunity to get rid of me. When I called the landlord company to ask about the discrepancy in the dates, they told me that the only person who could give me an answer would not be available until Monday, which would have been the day of my deadline.

I had to take the day off to go to the clerk’s office and join the long line of other New Yorkers holding pink slips of paper in their hands. Standing there, I thought back on the headlines that began appearing in the local papers at the beginning of the year, reporting electricity bill increases of as much as 300%. Over the course of the previous year, the median rent in New York City had gone up by about 25%, compared with a national increase of only 12%.

I wouldn’t have thought much of either of these facts in February, but when my rent increased a few hundred dollars in July to more than half my paycheck, a situation that as of a few years ago described more than 11 million Americans, I went into financial freefall. The inability to dig oneself out of a hole with a single paycheck is damning; there simply isn’t that much extra time to maneuver before the courts get involved.

I don’t know the circumstances of those in line with me at the clerk’s office that day. Some, I suspect, were similar to my own, which is to say manageable: in my case a years-long failure to align my expectations with my financial situation that at last became at least temporarily untenable. But while the worst outcome for me was ending up in my childhood bedroom in Ohio, with leftovers for dinner and borrowed car keys in my pocket, the line was far more perilous for those who had families, who had lost their jobs, who had incurred sudden and unexpected medical debt. For them, the past few years have been a nightmare: there are at present more than 2 million renter households in the city. In the previous 10 months, just under 10% of those were served with notices, about 10% of which were executed. The rest, if they couldn’t pull together their back rent, left.

During the worst of the coronavirus outbreak, several measures on the federal and local levels were enacted to curb evictions. And to a large extent they worked, keeping the number of filings at historic lows. But the last of these safeguards, a citywide moratorium on evictions, expired in January 2022. When it did, more than a third of low-income tenants reported being worried they would be evicted, and since then, the filing rates have more than doubled from the previous year. According to the New York City department of investigations, the number of evictions executed in the city has risen every month since.

When I phoned Andrea Shapiro, the director of programs and advocacy at the Met Council on Housing, to ask about the evictions since coronavirus, she told me the situation was worse than the numbers described: “Covid remarkably changed everything. People simply couldn’t pay their rent. No one could afford to live on their own,” she said. “People are moving around and the market allows landlords to raise rent dramatically really fast.”

The problem is not only that the renters lost their income during the pandemic, but that the process itself broke down. Many of the low-paid housing lawyers lost their jobs, or were forced to practice in a more lucrative field. From January to September of last year, the proportion of tenants facing eviction who had access to a lawyer reliably fell, week over week, from 54% to 6%; meanwhile, 98% of landlords had representation.

“The eviction process confuses people and for tenants there is no one really there,” Shapiro said. “The majority of people who get evicted in New York simply don’t show up. The problem is that there aren’t enough lawyers.”

When I reached the clerk’s window, I was surprised to find how kind he was as he set my court date. He told me that if I had any repairs or other complaints that my landlord had failed to address, I needed to tell him immediately; otherwise, they would be inadmissible at my hearing. I wondered how many people facing eviction didn’t find this out until they were before a judge, when it was too late. When I handed the clerk my passport, he noticed the US seal had worn off the front cover. “Now you can use it to go anywhere,” he joked, just in case things didn’t go well at court.

Later, at my hearing, I would find similar kindness from everyone involved. “That’s the banality of evil of bureaucracy,” Shapiro told me. “They feel bad. It’s not a good thing. But the judge decided your case could go forward without a lawyer. The government doesn’t make it a good enough job to be a housing lawyer. All of these people are involved but none of them are that mean. You can be evicted and say, ‘Everyone is sort of nice.’”

When I returned from California to New York, my savings were mostly gone. I moved in with a housemate, in a small room with a window facing an alley through which the sun shone for only about two hours around midday, when I was usually at work.

The place was beneath an apartment where spaghetti, laundry and dollar bills fell regularly from the windows and landed on our sills and fire escape. Water fell from our kitchen ceiling, too, a result of what seemed to be perpetual flooding upstairs. Our neighbor’s explanations grew more outlandish as time went on: at first, he would explain, he forgot the bathtub was running. Later, he claimed he was thawing a frozen turkey in the sink when it rolled over the drain, blocking it. He forgot about it too. Still, he was quick to come down with his tools and patch our ceiling. Today I look back fondly on this and other earlier living arrangements in my life. I wonder why these circumstances came to feel – and still sometimes feel – like they were a means to an end. What that end is I couldn’t say, beyond evoking the phrase “middle class”, which has proven as elusive for me to define as it has been to feel I’ve achieved.

As far as I can tell, my earliest notions of what the middle class is came from my own upbringing in north-east Ohio, which afforded me a sense of financial security that I had hoped to achieve again for myself as an adult. As a kid, I encountered all the worries I was fortunate not to have: when I bagged groceries at my town’s market, one of my co-workers for a few years was a woman in her 40s who would often softly ask if she could be the one to help certain customers. She was short on cash for the week, she’d explain, and she thought she might be able to sell this particular person a jar or two of the homemade liquor that she kept in the trunk of her car. I would find the same stress during the few months I was a telemarketer, where some of my fellow employees who had spent many years at the company were in constant fear of getting fired for making up orders. They couldn’t afford to lose their jobs, they told me, but nor could they stomach manipulating struggling elderly people into handing over portions of their social security checks, which was all but official company policy.

What all this adds up to, for me in New York City in my 30s, I can’t say. I put the question to Rakesh Kochhar, a senior researcher who studies class at Pew Research Center. He told me he defined “middle class” simply as those who make between 66% and 200% of an area’s median income, which for a one-person household is about $99,400 in New York City in 2023. The middle class is, by that definition, relatively stable. “Roughly two-thirds are in whatever income tier they were in a year ago,” he said. The remaining third have an equal chance of moving up or down. “It’s about a 50-50 shot.” By that measure, I fall just short of the middle class in New York.

The Brookings Institution, however, suggests multiple factors are at play in determining membership in the middle class: cash is one, of course. But so are “credentials” and “culture”. The importance of these latter two forces in my circumstances were clear when I was able to avoid eviction and pay off my back rent with the help of a grant to write this story. It was not a task I was eager to take on, in part because I don’t know what to make of the time since that first notice of overdue rent appeared at my door: of its implications for my future, of its roots in my past, of its relationship to the broader economic circumstances of my city. But reflecting on the previous 15 years, I see now that I stood to lose far more than an apartment on those trips to the courthouse. For many of the more than 200,000 households whose eviction cases have accrued from the pandemic, these losses will be realized.

I think of the people I shared that first house with, all so full of the feeling that the future hadn’t yet arrived. One housemate now lives not far from me, a successful poet in similar circumstances to my own. Another moved to Chicago and got a PhD. We lost touch. Another moved to Germany, befriended a wealthy club owner, and started a software company with him. We lost touch, too.

The last one, an artist, moved to a small village in Mexico. There, he said at the time, they all dressed as revolutionary soldiers and carried guns from a war long ago fought. “The house is pale red on the outside. It must have been bright red once,” he wrote to me. The last thing he said to me before we lost touch was: “I once found a dried up well with the skeleton of a dog inside, tied around the neck to a plastic bucket full of dust. The village was a great place to draw corpses, though I never did so. I lost motivation.” Mostly, what I remember from the time I lived with him was the black bean and plantain burgers he would make us on his night to cook dinner. And I remember the painting he spent the year working on in absolute secrecy. It turned out to be a demon giving birth to another demon. He went to Kinkos and spent his last few hundred dollars to make five giant, high-quality prints of it. He glued them to the inside of the doors of bathroom stalls at a handful of museums, including the Guggenheim and the Met. He later explained: people would spend more time at these museums sitting on the toilet staring at and thinking about his painting than they ever would spend standing before any Picasso or Hopper, no matter how many millions those people or those paintings were worth.

I wish I had seen it back then, sitting on that stained white couch, as we all tried to make our way. Now, I tell that story all the time.

For the moment, I’ve managed to keep my home. But everyone in my building hasn’t been so fortunate. A couple of months ago, in the frozen food section of my local supermarket, I ran into my neighbor from the third floor who collected used copies of the Times. He recognized me while he was asking for help reading the cooking instructions printed on the sides of boxes. He, along with 4,000 other tenants in the city that year, had lost his apartment. It is a situation that only stands to worsen for long-term renters like him, now that the city’s rent guidelines board has approved a 3.25% increase on leases for rent-stabilized units.

These days, he told me, he lives in a place with only a microwave in the kitchen. It wasn’t so bad, he supposed, but he was lonely. His pet birds had died, and worsening difficulty using his legs had made it hard to visit old friends, whom he’d concluded were busy with their own lives anyway. Most of all, he was worried over the habit he’d picked up of talking to himself. “I’m not someone who talks to himself,” he joked, as he filled his cart with three-packs of individual frozen cheese pizzas.

It’s just that there was no one around any more, and he still had so much to say.

This article was amended on 8 March 2023 to state that it was from January to September in 2022, not in 2023 as an earlier version said, that the proportion of tenants facing eviction who had access to a lawyer reliably fell from 54% to 6%.

Joe Kloc’s first book, Lost at Sea, will be published next year